The loss of biodiversity threatens national security, says a new government report – and Dorset is already feeling the effects

Wildlife populations are down by 73% since 1970. Freshwater species have fallen by 84%. These two examples are not just ‘nature loss’ – they are the

result of the sweeping erosion of the systems that feed and stabilise civilisation.

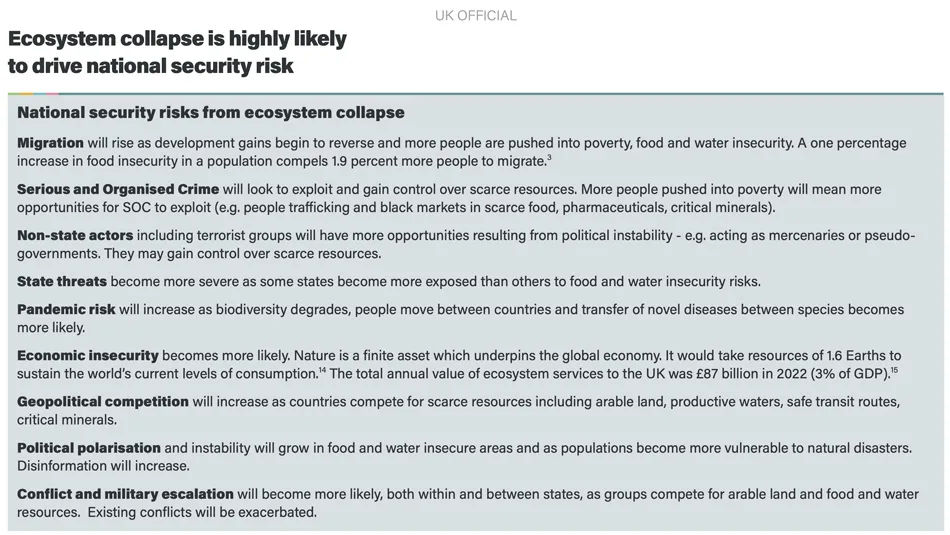

The Government’s new national security assessment, quietly released on 20th January, reaches a stark conclusion: global biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse are no longer ‘just’ environmental issues, but are direct threats to national security, economic stability and the food supply.

Using intelligence-style risk frameworks rather than academic modelling, the report warns with high confidence that ‘ecosystem degradation is occurring across all regions. Every critical ecosystem is on a pathway to collapse (irreversible loss of function beyond repair).’ The consequences are likely to include food insecurity and rising prices, alongside political instability, increased migration and conflict over resources.

Does it matter in Dorset?

For many people, the report feels distant – rainforests and coral reefs are a world away from rural Dorset. But according to Dorset Wildlife Trust (DWT), the impacts are already being felt much closer to home.

‘It can be difficult to envisage how nature loss somewhere else affects us locally,’ says Imogen Davenport, DWT’s director of nature-based solutions. ‘But we’re already seeing it with climate change. The security risks – food supply, political instability, migration – are happening now. The same applies to biodiversity loss. It will affect food prices, availability and the water cycle.’

One of the report’s clearest warnings is that when ecosystems break down, the consequences don’t stay local: fertile soils, clean water, pollination and climate regulation all unravel together.

These changes can be seen most quickly in the marine environment: ‘The ocean is more fluid – obviously,’ Imogen says. ‘Temperature and acidity shifts move quickly, and species respond by relocating.’ Off the south-west coast, octopus numbers have surged, tuna are appearing more frequently, while basking sharks – once a familiar sight – have largely moved north. ‘It’s not just about loss,’ she says. ‘It’s the speed of change. Add biodiversity decline, and the impacts multiply.’

On land, Dorset’s sheltered position as a southern county means it can become a refuge for species moving north – but that does not mean ecosystems are healthy.

‘We’ve seen long-term degradation to the point where systems struggle to function,’ Imogen says, pointing to Poole Harbour. Excess nutrients entering via rivers have fuelled algal growth that smothers mudflats and saltmarsh, weakening the entire system. ‘Once degraded, ecosystems are far less able to adapt.

‘It becomes a vicious circle.’

Farming or wilding?

The report identifies food production as the biggest driver of biodiversity loss on land – an uncomfortable finding in a county where farming is economically and culturally central. But Imogen firmly rejects the idea that food security and nature recovery are in conflict. ‘You can’t have a healthy food system without nature,’ she says. ‘If soil washes off fields into rivers, it’s not growing food – and it’s causing damage downstream.’

In some places, work is already under way to undo historic decisions – including more costly options like ‘daylighting’ rivers that were forced into underground sewers decades or even centuries ago.Restoring ecosystems, the report argues, is often cheaper and more reliable than technological fixes applied after failure. Imogen agrees – with caveats. ‘There’s definitely some fantastic uses for technology, but some of the ‘fixes’ we’ve used historically have made things worse,’ she says. ‘Simply adding more fertiliser to degraded soils just means more nutrients end up in rivers.’

Restoring natural watercourses can reduce flooding and pollution, and can be simple where water is given the space to establish wetlands. In some places, work is already under way to undo historic decisions – including more costly options like ‘daylighting’ rivers that were forced into underground sewers decades, or even centuries, ago.

Water sits at the heart of the issue. Dorset has swung between drought and flooding in the past year, exposing how fragile its landscapes have become.

‘If we keep water closer to where it falls – slowing it, holding it in soils and wetlands – we reduce flood risk, recharge supplies and help nature at the same time,’ she explains.

Much of that thinking is embedded in Dorset’s Local Nature Recovery Strategy. ‘The challenge isn’t the ideas,’ Imogen says. ‘It’s implementation. These are big, interconnected jobs that require commitment across sectors.’

Framing biodiversity loss as a national security risk could now sharpen that commitment – but only if it changes decisions on planning, land use and infrastructure. The report’s warning may be in the language of global risk and national security, but its impacts are felt in Dorset’s stressed landscapes and harbours, in the heated debates about farming vs. development.

The distance between those global warnings and everyday life in Dorset is shrinking fast.

Read the Nature Security Assessment on Global Biodiversity Loss, Ecosystem Collapse and National Security in full here