A 1938 postcard captures Cerne Abbas in a quiet in-between moment: after decline, before revival – when the Giant didn’t warrant a mention

In his 1906 book Highways and Byways in Dorset, Sir Frederick Treves painted a bleak picture of Cerne Abbas as ‘decaying and strangely silent’: ‘It is a clean, trim, old-world town, which has remained unchanged for Heaven knows how many years … The place, however, is empty and decaying and strangely silent. Grass is growing in the streets; many houses have been long deserted.

‘One feels compelled to walk very quietly through the echoing streets, and to talk in whispers, for fear that the sleep of Cerne should be broken.’

Treves concluded, bluntly, that ‘Cerne Abbas is dying’, its vitality lost, he believed, when the railway reached Dorchester and the coaching traffic that once used the village as a staging post disappeared. Attempts to reinvent the town as a centre of manufacturing failed and, by the end of the First World War, the Pitt-Rivers family – faced with heavy death duties – decided to sell it from their estate.

On 24th September 1919, some 4,700 acres of ‘residential, agricultural and shooting’ land were auctioned at Dorchester Town Hall in 75 lots. Present was Frederick Harvey Darton – publisher, Dorset devotee and author of The Marches of Wessex – who toured the properties beforehand and found the same level of decay Treves had noted more than a decade earlier.

It was a reality the auctioneers’ catalogue failed to mention, preferring what now read as rather familiar estate-agent phrases such as ‘well-constructed small private residence’ and ‘pretty creeper-clad cottage’.

Darton later described the sale itself: ‘It was full, quite full, of farmers, with a sprinkling of gentry… There was a subdued undercurrent of feeling which could not be mistaken: it broke out in cheers when a tenant bid successfully.’

A small number of tenants did manage to buy their homes – the butcher, baker and a shopkeeper among them – but fewer than a quarter of the lots went to sitting tenants, many of whom were already relatively well off. Some cottages sold for under £100; the medieval jetty-fronted houses of Abbey Street went for just £340.

The Swanage Times reported that ‘over £95,000 was realised at the sale’. One of the chief properties, the Melcombe Estate, was bought by Mr Clough of Burley, Ringwood, for £29,250. Barton Farm was purchased by its tenant, Mr J Sprake, for £12,300, while The Abbey House, with guest house, gatehouse,

Abbey site, outbuildings and 196 acres which included Giant Hill sold for £7,600.

The sale may have helped the Pitt-Rivers estate finances, but it did not halt Cerne’s decline. Maintenance proved beyond many of the new owners, pigs were reported living in Abbey Street houses, and within a decade the population had fallen to around 450.

Yet from the 1930s onwards, Cerne began to recover. New residents arrived in search of tranquillity, restoration followed and the village slowly found a new footing. Today, with housing developments on the village edge and revived local amenities, the transformation is striking. Once written off as dying, Cerne has long since proved Treves wrong.

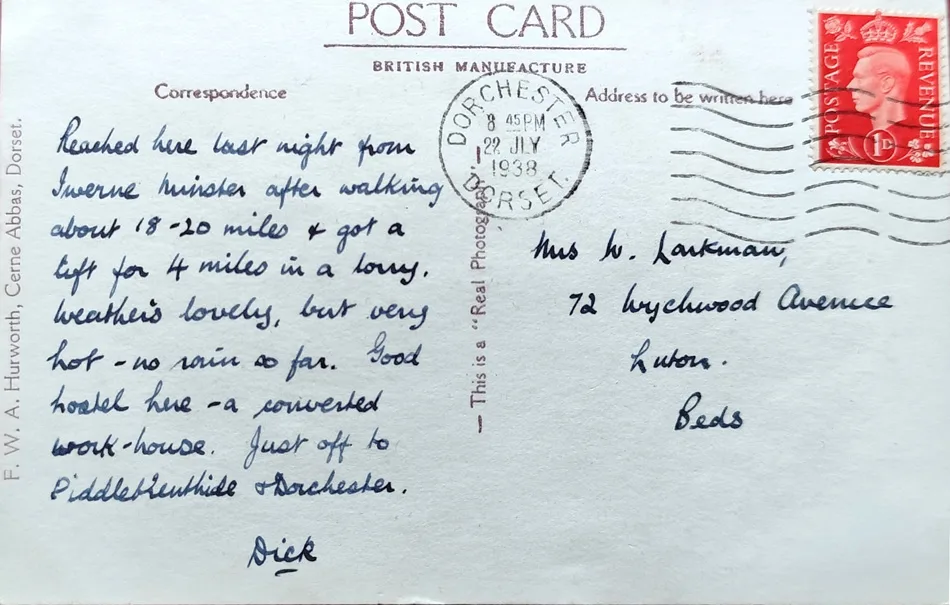

The postcard, sent from the village on 22nd July 1938, captures something of that quieter, transitional period. Writing after a long walk in summer heat, the sender noted the ‘good hostel here – a converted workhouse’. Between 1932 and 1955, the former workhouse served as a youth hostel; during the Second World War it housed evacuees from a London school, before later becoming flats. It is now a residential care home.

‘Reached here last night from Iwerne Minster after walking about 18-20 miles & got a lift for 4 miles in a lorry. Weather’s lovely, but very hot – no rain so far. Good hostel here – a converted work-house. Just off to Piddletrenthide & Dorchester. Dick’