Monographs from the Toucan Press collection: interviews with people who knew Thomas Hardy, from royalty to his parlour maid

In the early 1960s, there were still many people living in Dorchester and across West Dorset who had known Dorset’s greatest writer, the poet and novelist Thomas Hardy.

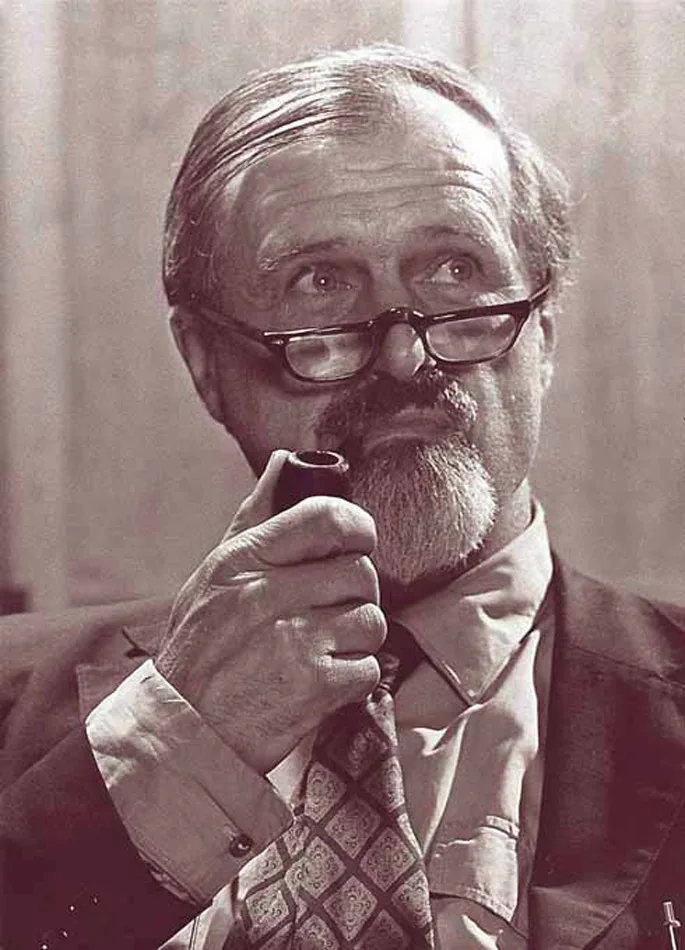

James Stevens Cox*, a Bristol-born antiquarian, historian and bookseller, had recently moved from Ilchester in Somerset to a house in Beaminster.

James, a polymath with an insatiable curiosity, realised that the recollections of these now-ageing locals would be invaluable for anyone interested in the writer. His decision to interview many of them was an act of amazing foresight – at that time Thomas Hardy was largely forgotten (outside Dorset). The memories, recorded in a series of monographs published by James’s Toucan Press, have provided a great deal of source material for subsequent biographies.

This is the first of a new series, drawing on James Stevens Cox’s interviews and researches into the life and times of Thomas Hardy. We begin with Thomas Hardy as a musician, recalled by a gifted Dorset-born pianist, Vera Mardon (née Stevens, no relation), who regularly accompanied Hardy at his home, Max Gate, while he played his violin.

Tim Laycock, Dorset’s much-loved musician, actor, historian, singer and Thomas Hardy and William Barnes expert, contributes some thoughts on Hardy’s importance in the revival of West Gallery Music and other Dorset folk songs and dances.

Vera was only 11 when she first met Hardy: ‘I clearly remember the occasion. It was at one of the early rehearsals by the Hardy Players for The Mellstock Quire, in the Town Hall.’ She was introduced by her father, EJ Stevens, who was an active member of the Dorchester Debating Society, of which the great writer was an honorary member. The production featured some old country dances but Hardy was unhappy with the dance: ‘He took a lady as his partner and then, despite his age (77), he nimbly demonstrated to the assembled company the correct steps and positions,’ said Vera.

He wasn’t impressed with the accompanist either: ‘He was displeased with the tempo and, borrowing the violin, he played in a lively manner all the required tunes from memory.’ He was a perfectionist, said Vera: ‘Everything had to be as he wanted it to be – correct to the smallest detail.’

‘Gee, Mr Hardy!’

Vera became Hardy’s accompanist after she finished her piano and violin studies at the Royal Academy of Music in 1918. Mrs Hardy (his second wife) invited her to come to Max Gate and Hardy asked her to play the piano while he played old dance tunes on his fiddle.

She recalls the pattern of the music sessions: ‘I arrived about 4.45 and had tea. This consisted of home-made cakes and very small dainty sandwiches. Afterwards I accompanied Hardy for about an hour and then I told him I ought to return home … Tea had been more of a ritual than a meal and at at that time I looked on it as an afternoon custom of the middle-class, not for the purpose of nourishment, but to provide a suitable background for a social chat. At the age I then was I had an appetite which the dainty fare could not satisfy.’

Although Hardy showed no interest in Vera’s classical studies he was interested in her violin, made in 1796 by the renowned Salisbury maker Benjamin Banks. Hardy had an old fiddle which he first saw in a shop window in London while he was a student – he had saved up for months and finally bought it.

While he enjoyed playing music, loved the theatre, adapted many of his stories and some of the novels for the stage and took a keen interest in the productions, he was very shy, and ‘lived in mortal terror of hearty extroverts, especially American ones.’ Vera recalls a visit by the Hardy Players to Glastonbury to see an operatic version of The Queen of Cornwall, Hardy’s verse tragedy based on the medieval legend of Tristan and Iseult. The opera was written by Rutland Boughton, the composer and founder of the original Glastonbury Festival.

At this time, two American ladies were visiting Dorset, keen to meet the famous writer and visit places associated with him. Vera’s father invited them to join the Hardy Players on their Glastonbury visit, but did not tell them that Hardy would be there too. He was concealed in a small room from where he could see the stage. ‘Unfortunately, one of the good ladies was very tall and she spotted him and enthusiastically rushed towards him, quickly followed by her friend, and thrusting out her hand said: ‘Gee, Mr Hardy! May I have the honour of taking you by the hand?’ Oh dear, it was a frightening moment.

‘Hardy was caught in just the situation he always dreaded. He very reluctantly allowed her to shake him momentarily by the hand, quietly muttering “Oh yes” then quickly jerked his hand free and rapidly turned on his heels and shot out of the hall to his hired car, at what, even for him, was a remarkably fast pace. He reminded us of a frightened rabbit scurrying back to its burrow.’

Going the rounds

Thomas Hardy grew up with family memories of the West Gallery music which his father and grandfather had played. It was generally metrical psalms, with a few hymns and anthems that were sung and played in Church of England parish churches, as well as nonconformist chapels, from 1700 to around 1850. The galleries where the choir (predominantly male, local amateur musicians and singers) played were 18th century wooden structures at the west end of a church or chapel.

The West Gallery Music Association website

(wgma.org.uk) gives a clear background to West Gallery music and its decline, described so poignantly (and humorously) in Hardy’s Under the Greenwood Tree. It explains ‘the determined Victorian effort of both parliament and the church to gain authority: animal cruelty sports were suppressed; old traditions such as Shrovetide football (seen as, and often truly little more than, riots) were put down; churches were “restored” and in 1861 Hymns, Ancient and Modern replaced the old musicians’ books of psalms and hymns, lovingly copied-out in manuscript.’

Eventually, ‘the old quire played no more’ – organs replaced bands, the historic and often quaint instruments were scrapped and the tune books burned. The Victorian dislike of the Georgian period galleries led to the removal of many, though Dorset has a number of churches that still have west galleries, including St Nicholas at Abbotsbury, St Mary’s at Puddletown, St Michael’s at Stinsford and the tiny ancient St Andrew’s at Winterborne Tomson. Several also retain box pews.

Tim Laycock, well-known for his performances as both Thomas Hardy and William Barnes, and with the Ridgeway Band and Singers, recalls his introduction to this music: ‘The starting point to the world of West Gallery music and the life-affirming world of community music for me and for many others was the opening chapters of Under the Greenwood Tree. Hardy’s masterful preface to the story sets the scene beautifully, and conveys perfectly the pride, dedication and sense of belonging that ‘Going the Rounds’ encapsulated.’

The tradition of Going the Rounds, described with such affection and colour in the novel, was revived by West Gallery and Hardy experts Mike Bailey and Furse Swann and continues as a biennial event in December, organised by folk musician Alastair Braidwood and the Thomas Hardy Society, retracing the carolling of the Mellstock Quire from Hardy’s cottage to the church at Stinsford with input from The New Hardy Players and the Ridgeway Singers and Band.

Old William Dewey instructs the men and boys of the Mellstock Quire: ‘Now mind, neighbours,’ he said, as they all went out one by one at the door, he himself holding it ajar and regarding them with a critical face as they passed, like a shepherd counting out his sheep. ‘You two counter-boys, keep your ears open to Michael’s fingering, and don’t ye go straying into the treble part along o’ Dick and his set, as ye did last year; and mind this especially when we be in “Arise, and hail.” Billy Chimlen, don’t you sing quite so raving mad as you fain would; and, all o’ ye, whatever ye do, keep from making a great scuffle on the ground when we go in at people’s gates; but go quietly, so as to strike up all of a sudden, like spirits.’

As Tim Laycock says: ‘Dorset is unique in having an internationally renowned writer who was also a folk fiddler and a great chronicler of the music, song and dance that inspired his father and his grandfather in their music making … What a fantastic legacy to leave!’

Next month: The revival of the West Gallery tradition, with memories of Tim Laycock and Dave Townsend, leader of the Mellstock Band

The annual Tea with William Barnes event, with Tim Laycock, Phil Humphries and the Ridgeway Singers and Band, takes place at the Exchange at Sturminster Newton on Sunday 22nd February at 3pm.

- James Stevens Cox (1910-1997) was my uncle – knowing my love of Hardy from an early age, he sent the monographs as they were published; permission to quote from them has been given by his son, Gregory Stevens Cox © Toucan Press